God in the queue: Why Bruegel’s painting shows no Christmas glory

About the coldest and most honest Christmas painting – one that teaches us to see hope amid bureaucracy, war, and winter.

We are used to seeing Christmas in paintings as something cozy. Golden straw, the warm glow emanating from the Child, shepherds kneeling, angels singing “Glory to God in the highest” (Luke 2:14). It is beautiful. It comforts. But at times – especially now, when winter outside feels anxious and the soul itself is full of drafts – such postcard images seem painfully distant.

We need another kind of truth. And five hundred years ago, Pieter Bruegel the Elder gave it to us.

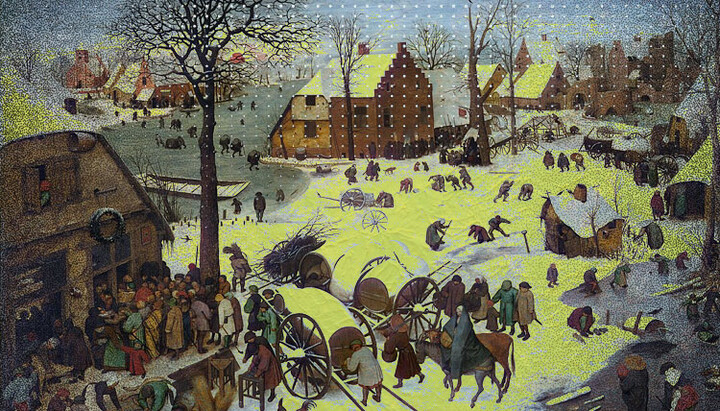

If you stop before his canvas “The Census at Bethlehem,” the first thing you feel, almost physically, is the cold.

There is no festive mood here. This is a raw, piercing Flemish winter of 1566. Above the snow-covered village hangs a heavy red setting sun. It does not warm. It looms like a heated coin, barely breaking through the frozen haze.

The branches of the trees are black and bare, like cracks in old plaster. The ice on the river is greenish-gray, trampled by hundreds of feet.

This cold is painfully familiar. It is the cold of an inhospitable world, where the small human being is always shivering. Bruegel does not embellish reality. He shows life as it is – harsh, dirty, and endlessly weary.

Bureaucracy instead of a miracle

We see bustle everywhere. Dozens of people crowd near a large house on the left. But this is no celebration. It is a queue.

Emperor Augustus has issued a decree for a census. Every family must return to the city of its ancestors to pay taxes. And so these people, abandoning their daily concerns, have trudged through frost and mud to hand their money over to the state.

Before us is the absolute power of bureaucracy. A clerk in a fur hat sits at a table, writing in a thick ledger. For him, people are merely numbers, lines in a report, taxable units.

Around him, heavy everyday life seethes. Someone is slaughtering a pig to store meat for winter. Someone drags a bundle of firewood. Children mill about underfoot, tangled in the hems of adult clothing.

If you look closely, you notice a disturbing detail – soldiers with spears stand near the walls and among the crowd. For Bruegel’s contemporaries, this was a frightening hint. He painted the canvas at a time when his native Netherlands groaned under Spanish occupation. These soldiers are a symbol of brute force.

The world in the painting lives in fear and tension. Everyone is occupied with survival.

All hurry to get their names recorded, just to be left alone. Each of us knows this feeling of helplessness in a long line for some certificate, this sense that you are nobody before the vast machinery of the state.

God incognito

The painting is called “The Census at Bethlehem.” But as we look at it, we are puzzled – where, in fact, is Bethlehem? Where is Mary? Where is Joseph?

Before us is an ordinary Flemish village. Hundreds of figures, absorbed in themselves. We search for the familiar center of composition – radiance, halos, exaltation. But there is none.

And here Bruegel makes his brilliant move. He forces us to search intently for God.

At the very center of the painting, yet astonishingly easy to miss, a pair is moving forward. A woman in a blue cloak, tightly wrapped against the wind, sits on a donkey. A man leads it by the reins. He is stooped, with a large carpenter’s saw on his shoulder, and a bull trudges nearby.

This is the Holy Family. And no one pays them any attention. Absolutely no one.

For the surrounding crowd, they are just more migrants. Another pair of newcomers who need a place to sleep. Joseph looks utterly exhausted. He does not know where they will sleep tonight. Mary is probably freezing; she is about to give birth, yet no one yields her the way. The carpenter’s saw on Joseph’s shoulder is not a symbol – it is his tool, his means of earning bread.

The blue of silence

Bruegel works with color here in a remarkable way. The entire painting is rendered in ochre, rusty, brownish tones – the colors of clay, old wood, dirty snow. The colors of earth.

And only at the center does a patch of pure, deep blue flare up – Mary’s cloak.

This blue feels foreign amid the rusty commotion. It is cold, yet strangely magnetic. It seems that all the chaos of the painting – merchants’ shouts, dogs barking, carts creaking – falls silent at this very point. Light here does not descend from heaven in rays. It emanates from this stillness itself. From the careful way Joseph leads the donkey. From the way Mary shields her face from the wind.

Light from the queue

In this silence of Bruegel lies his greatest consolation for us. The artist tells us: the most important event in the history of the universe happened precisely like this. Without fanfare. Without red carpets.

God entered the world through the back door. He did not come to the palace of the emperor who ordered the census. He came into the queue. He became one of those who are registered, taxed, jostled with elbows. He dissolved into the crowd of weary people.

When we look at “The Census,” we stop expecting special effects from God. We begin to understand that He acts differently. He enters our cold, our domestic disorder, our fears and our problems with documents – and illuminates them from within.

If you now feel small, exhausted, and unwanted in the vast queue of history, do not be afraid. Look at Bruegel’s painting.

Christ is not somewhere far away, in unreachable heavens or golden halls. He is here. In a blue cloak, amid snow and bureaucracy. He is standing in this queue together with us. And that means we are not alone.