Venerable Anthony: The saint without whom Kyiv would not stand

"No village stands without a righteous man, and no city without a saint." One of the spiritual pillars of Kyiv is Venerable Anthony of the Caves. With this article, we continue our series of publications about the Lavra.

A Word About the Sources

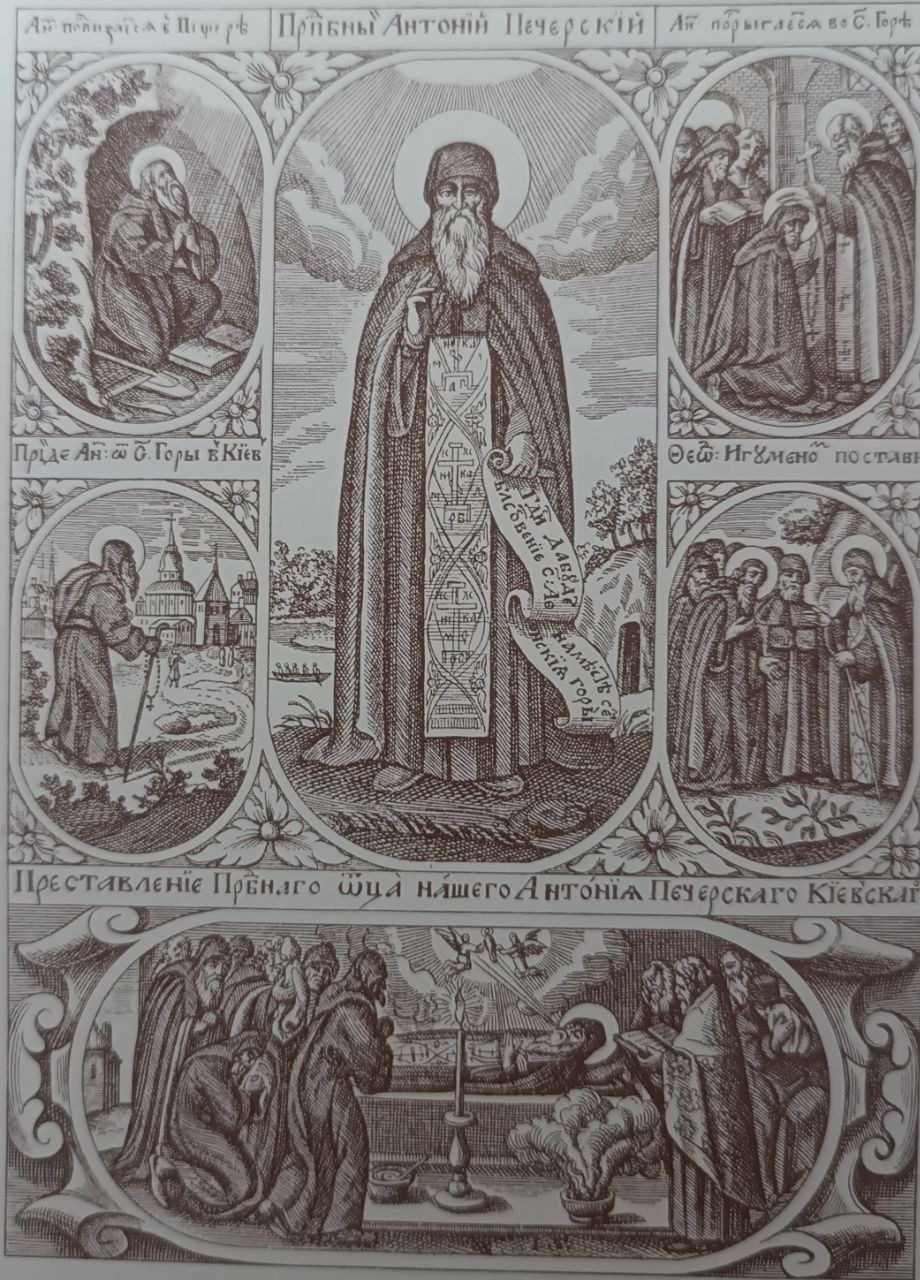

When describing the life of Venerable Anthony of the Kyiv Caves, it must be acknowledged that there are few precise facts about his life that are confirmed across various sources and remain beyond doubt. What we do know with certainty is that Anthony was born in the town of Liubech near Chernihiv, took monastic vows in one of the Athonite monasteries, later returned to Rus’, and settled in a Varangian cave on the banks of the Dnipro River. Before long, a few disciples gathered around him: Moses the Hungarian, Nikon, Barlaam, and Ephraim.

Having appointed Barlaam as abbot of the monastery, Saint Anthony withdrew into a cave hermitage, where he spent the remaining 40 years of his life. We also know that he left Kyiv twice due to disagreements with Prince Iziaslav. Everything else in his life story is a matter of scholarly reconstruction: a piecing together of data from various sources, assumptions in cases of discrepancy, and the inclusion of later traditions. This doesn’t mean these details are fictional – only that their credibility is relative. His Life was written not long after his repose, no later than the 1090s, but the original has not survived; what we have today are fragments and reconstructions.

Scholars distinguish between two traditions of Anthony’s biography: the “Antonian” and the “Theodosian.” The former relies primarily on the Primary Chronicle, specifically the section titled The Tale of Why the Monastery Was Called the Cave Monastery (1051), and the Kyiv-Pechersk Patericon (earliest version – late 11th century). The “Theodosian” tradition draws on references to Anthony in the Life of Saint Theodosius of the Caves (late 11th – early 12th century), along with the Primary Chronicle.

Early Years

Saint Anthony was presumably born in 983, i.e., before the official baptism of Rus’ by Prince Volodymyr in 988. Despite this, it appears his family was already Christian. One source says: “From a young age he was filled with the fear of God,” indicating he believed in Christ from childhood. Later sources assert that he began ascetic practices from an early age and even dug himself a cave near Liubech for that purpose. In 1870, a monument was erected near this cave, and an annual procession has since been held there. His secular name may have been Antipa, but this is mentioned only in one late (13th-century) copy of the Primary Chronicle.

At what age Anthony journeyed to Mount Athos is unknown – perhaps in his youth. The monastery where he took monastic vows and performed his ascetic feats is also uncertain. The hypothesis that it was the Monastery of Xylourgou, where monks from Rus’ resided, is just speculation. Claims that he was tonsured at the Great Lavra of Saint Athanasius or at Esphigmenou Monastery are found only in very late sources from the 18th–19th centuries. One thing, however, is beyond doubt: Anthony absorbed the spirit of Athonite monasticism and became an Orthodox ascetic deeply rooted in the Byzantine tradition. His entire life thereafter testifies to this.

Return to Rus’

.jpg)

After some time (how long is impossible to determine), Anthony returned to Rus’. The Laurentian Chronicle states that the Athonite abbot, having taught him the monastic way of life, said: “Go back to Rus’, and be a blessing from the Holy Mountain, for through you many monks will come to be.” But upon returning home, Anthony did not act in a way that might logically lead to founding Russian monasticism. A practical man might have approached the local Kyiv princes to seek resources, attract monks, and establish a grand monastery with majestic services. Instead, he did the opposite – he went into a cave.

Later, the venerable chronicler Nestor wrote that Anthony, having visited the monasteries of Kyiv, “was not pleased with a single one, as God did not will it, and so he began to wander through forests and hills, seeking the place God would show him.”

No “efficient manager” would act like this. The monasteries Anthony visited were princely foundations – landed estates established by rulers and nobility to affirm their own status. They were populated by monks living without rules or discipline, practicing monasticism each in his own way.

Anthony, by contrast, knew what true monastic life required, had learned established rules, and could have turned these aristocratic institutions into genuine monastic communities in the Byzantine spirit.

But instead, he hid himself in a cave beyond the city limits of old Kyiv, in Berestove – in a cave dug either by Varangian raiders or by the priest Hilarion, who would become Metropolitan of Kyiv. In this, we see Anthony’s authentic monastic spirit – his trust in God, not in worldly powers. He believed that monasticism in Rus’ would be established by the Lord Himself, and that he, Anthony, was merely a tool of Divine Providence. He was committed to living the ascetic life he had learned on Athos and would not compromise its ideals for the sake of princes or their courts.

Determining the year of Anthony’s return to Rus’ is complicated. The “Antonian” tradition claims it was no later than 1030, while the “Theodosian” tradition places it no earlier than 1051. An attempt to reconcile these two led to the theory that Anthony made two trips to Athos and returned twice. Supposedly, after his first return, he was alarmed by the internecine conflicts among the sons of Prince Volodymyr for control of Kyiv and withdrew again to Athos.

However, since Volodymyr died in 1015, Anthony would have had to arrive in Kyiv even earlier – and we have no records of that. Moreover, a monk-hermit would hardly have been frightened by princely strife.

Most historians consider the “Theodosian” tradition more reliable. According to it, Anthony returned to Rus’ no earlier than 1051 and settled near Berestove in a cave believed to have been dug by Saint Hilarion, later Metropolitan of Kyiv.

Hilarion was appointed metropolitan in 1051 or early 1052. Chronicles describe his activities in that role: his involvement in issuing Prince Yaroslav’s Church Statute, the consecration of the Church of Saint George in Kyiv, and the ordination of Leontius as bishop of Rostov and Suzdal. After that, references to Hilarion disappear. By 1055–1056, the Novgorod Chronicle already names the next Metropolitan of Kyiv, the Greek Ephraim.

There is no mention of Hilarion’s death or burial, though such a significant event would likely have been recorded. This absence has led to a plausible theory: that the Greeks disapproved of Hilarion’s appointment as metropolitan by Rus’ bishops under Prince Yaroslav and sent Ephraim to replace him. Hilarion then withdrew to the same cave near Berestove where Anthony had settled.

Some identify Metropolitan Hilarion with the Venerable Hilarion the Schema-monk, who died in 1074. However, a more likely theory is that Hilarion became the monk Nikon – one of Anthony’s first disciples, whom Anthony entrusted with tonsuring new monks into the emerging Pechersk Monastery. According to this theory, Nikon was Hilarion’s name in the Great Schema. That said, this version also has serious objections.

The First Persecution

Whatever the exact chronology, Saint Anthony’s community soon faced a great trial. In 1054, Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise died, and his son Iziaslav ascended the throne of Kyiv. Some of Iziaslav’s close courtiers, having encountered Anthony and witnessed his ascetic life in the cave, were inspired to become monks. Among them were Ephraim, a favorite of the prince, and Barlaam, son of the prince’s chief nobleman and military commander, Yan Vyshatich. Anthony accepted them into his community and instructed the venerable Nikon to tonsure them. Naturally, this provoked the anger of both Prince Iziaslav and Yan Vyshatich.

This incident once again illustrates how deeply spiritual – rather than pragmatic – Anthony and his disciples were. From a worldly perspective, receiving such high-ranking individuals into the monastery without the prince’s permission was an open invitation to disaster. And disaster came swiftly.

“When Prince Iziaslav learned what had happened with his nobleman and his eunuch, he was furious and ordered the one who dared to do this brought before him. Immediately they went and brought the great Nikon to the prince. The prince, in his anger, turned to Nikon and asked: ‘Was it you who tonsured my nobleman and my servant without my permission?’ Nikon replied: ‘By the grace of God, I tonsured them, by the will of the Heavenly King, Jesus Christ, who called them to this path.’ The prince said: ‘Either convince them to return home, or you shall be imprisoned along with your companions, and your cave shall be sealed.’ Nikon answered: ‘My lord, if that is your will – do as you must. But it is not fitting for me to turn away warriors of the Heavenly King.’ Then Anthony and all his companions took their robes and left their place, intending to go into another land. While the prince was still reproaching Nikon, one of his servants came and reported that Anthony and the others were leaving the city for another land. At that moment, the prince’s wife said to him: ‘Listen, my lord, and do not be angry. A similar thing happened in our own country: when the monks were driven out due to some misfortune, that land suffered greatly. Beware, my lord, lest the same befall your realm.’ Hearing this, the prince grew fearful of God’s wrath and released the great Nikon, ordering him to return to his cave. He then sent after the others, instructing them to return with prayers. It took nearly three days of persuasion before they came back to their cave…”

(*Life of Saint Theodosius of the Caves*)

The wife of Prince Iziaslav mentioned here was the Polish princess Gertrude (known in Orthodoxy as Elena), a deeply pious woman and author of a collection of prayers. She revered Saint Anthony and later founded the women’s Monastery of Saint Nicholas in Kyiv, where the mother of Saint Theodosius eventually retired. The calamities that befell Poland, which she warned Iziaslav about, were real events that occurred when Prince Bolesław expelled monks from the land.

Gertrude’s intervention calmed the prince’s wrath. However, Barlaam’s father, the military commander Yan Vyshatich, upon learning of the incident, “came to the cave with many retainers in fury, scattered the God-chosen flock of Anthony, dragged out his own son, the blessed Barlaam, tore off his monastic garments, dressed him in nobleman's robes, and forcibly returned him to his chambers” (*Life of Saint Ephraim of the Caves*). Thus, the Pechersk community did indeed suffer a kind of dispersion.

Following this conflict, the venerable Nikon left the monastery and went to Tmutarakan (present-day Taman in Russia’s Krasnodar Krai), where he founded the Monastery of the Most Holy Theotokos.

Saint Anthony himself withdrew into seclusion, but not before appointing Barlaam as abbot, who eventually succeeded in persuading his father to let him return to monastic life.

Barlaam is considered the first abbot of the Caves Monastery, as up to that point the community lived without formal leadership. Saint Anthony was its spiritual mentor but did not wish to burden himself with administrative duties. For his solitude, Anthony dug a new cave – now known as the Near or Anthony's Caves and left the older cave (the Far Caves of Saint Theodosius) to the brotherhood. But the number of brethren quickly grew, and space became scarce. Anthony then blessed the construction of a Church of the Dormition above the cave, as well as cells for the monks and a surrounding wall.

All of this became possible after Anthony petitioned Prince Iziaslav to grant the monastery the hill above the cave – and received his consent.

The Second Persecution

In 1068, the well-known Battle of the Alta took place, in which the sons of Yaroslav the Wise – Iziaslav, Sviatoslav, and Vsevolod – were defeated by the Polovtsians under Khan Sharukan. According to some accounts, Saint Anthony foretold Iziaslav's defeat in the battle, which hardly endeared him to the prince. After the battle, Iziaslav and Vsevolod returned to Kyiv, where the citizens demanded that arms be distributed to the people to continue resisting the Polovtsians, who were pillaging the land with impunity.

The people convened a veche (a kind of public assembly or, in modern terms, a maidan) and addressed Prince Iziaslav: “The Polovtsians are scattered throughout the land – give us weapons and horses, prince, and we will fight them again.” But the prince refused. This sparked the Kyiv Veche Uprising of 1068. Iziaslav fled to Poland, and the veche appointed his nephew, Prince Vseslav of Polotsk (not to be confused with the Polovtsians), who had been held in captivity in Kyiv, as ruler.

It is unknown what kind of relationship Vseslav had with Saint Anthony, but when Iziaslav managed to return to Kyiv with the help of the Polish prince Bolesław II, the following occurred: “At that time, Prince Iziaslav came back from Poland and grew angry with Anthony because of Vseslav. Then Sviatoslav, having sent word, had Anthony secretly sent to Chernihiv at night. Anthony, arriving in Chernihiv, came to love the Boldyni Hills; he dug a cave there and settled. And there stands to this day the Monastery of the Holy Theotokos on the Boldyni Hills.” (*Primary Chronicle*)

In essence, the events mirror what we see today in the relationship between the Ukrainian Orthodox Church and the Ukrainian state. In the 11th century, the state – represented by Prince Iziaslav – suspected Anthony of political disloyalty and subjected him to persecution. In the 21st century, the Ukrainian authorities accuse the UOC of being "pro-Russian" and likewise persecute it.

Then, as now, these suspicions are unfounded. Just as the cave-dwelling hermit Anthony posed no threat to Iziaslav’s political ambitions, so too the UOC today poses no threat to Ukrainian statehood – in fact, it accepts and supports the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine. Yet then and now, the authorities fail to understand that the Church’s interests lie in an entirely different realm – the spiritual. The Church’s mission reaches far beyond the bounds of earthly affairs; Christ’s Kingdom is not of this world: “My kingdom is not of this world…” (John 18:36).

In Chernihiv, Anthony dug caves very similar to those at the Lavra. They include cave churches, a refectory, and cells, with a total length of about 340 meters. This striking similarity strongly confirms Anthony’s presence in Chernihiv.

Return to Kyiv and Blessed Repose

Most likely, Anthony returned to Kyiv no earlier than March 1073, after Iziaslav had once again been driven out to Poland by his younger brother, Sviatoslav Yaroslavovych, who ruled in Kyiv until 1076. The venerable Anthony reposed soon after his return. However, he lived to participate in the founding of the stone Dormition Cathedral of the Pechersk Monastery, the location of which was revealed to him by God after long prayer.

According to his will, he was buried in the Near Caves, close to his cell and the cave church later consecrated in his honor. The saint strictly forbade the opening of his relics or their public veneration. Considering how in 2023 the “Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra Reserve” declared the relics of the Pechersk saints to be “museum exhibits” and the property of “the people” (most of whom are far from the Church), one is once again convinced of how right Saint Anthony was.

The Patericon includes a tale of how, when some monks once attempted to uncover the saint’s relics, they were struck blind. In the book *Teraturgima* by Athanasius Kalnofoisky, a monk of the Caves (dated 1638), it is said that a certain “Muscovite” tried to seize Anthony’s relics. What exactly happened is not entirely clear.

Afterword

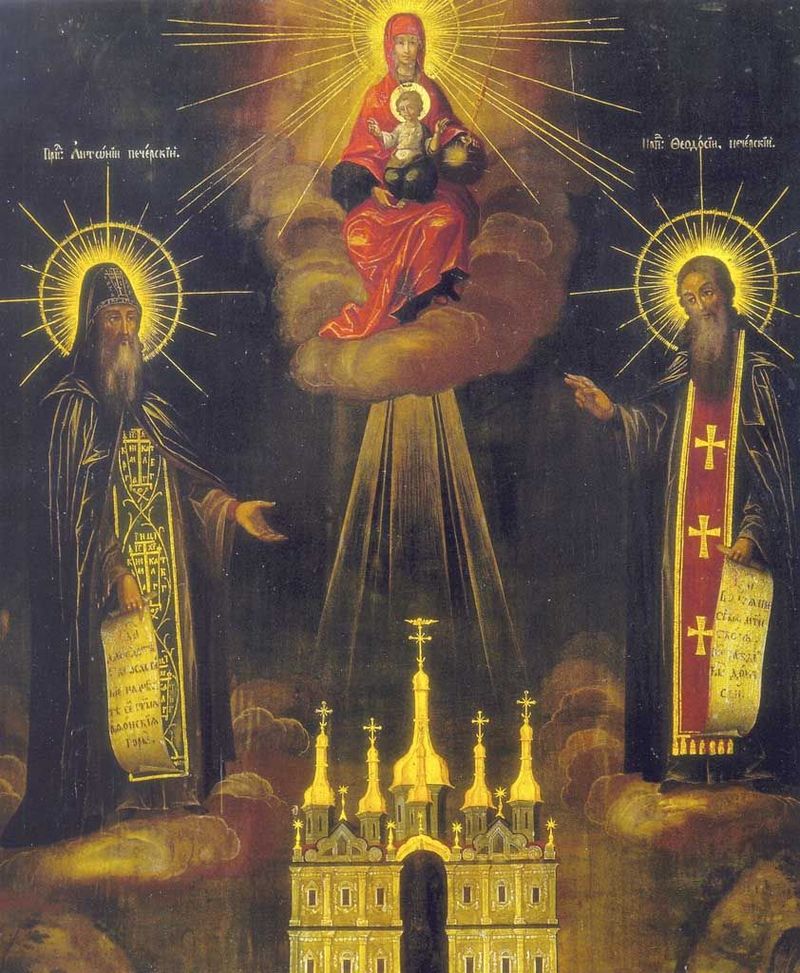

Veneration of Saint Anthony appears to have begun almost immediately after his repose, as evidenced by the early composition of his *Life*. By the 12th century, icons of Anthony and Theodosius were already known. The importance of Saint Anthony – for Kyiv, for our nation, for monastics, and for all Orthodox faithful – is hard to overstate. He withdrew into a cave, fled from the world, yet the world came to him, instinctively sensing the holiness of this man, the radiance of the Holy Spirit within him, which poured forth on all who came to him – and continues to do so today through prayer.

The monastery he founded became a beacon of Christian faith in our land. From it came forth dozens of hierarchs who brought the Gospel to the most remote corners of the land. What is happening today with the Lavra wounds our hearts deeply: Saint Anthony was persecuted in his lifetime – and now, nearly a thousand years later, he is persecuted again. “Indeed, all who desire to live godly in Christ Jesus will suffer persecution” (2 Timothy 3:12). But just as the venerable one did not abandon his faith and monastic ideals then, so too must we today remain faithful to Christ and His Church – and that will be the most worthy way to honor the memory of Saint Anthony.

Venerable Father Anthony, pray to God for us!